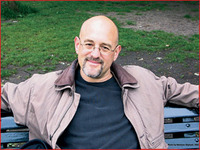

author

authorDiscover the Best Books Written by Carl Rogers

Carl Ransom Rogers was an American psychologist and of the founders of the humanistic approach (and client-centered approach) in psychology. Rogers is widely considered one of the founding fathers of psychotherapy research. He was honored for his pioneering research with the Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions by the American Psychological Association (A.P.A.) in 1956.

The person-centered approach, Rogers's unique approach to understanding personality and human relationships, found wide application in various domains, such as psychotherapy and counseling (client-centered therapy), education (student-centered learning), organizations, and other group settings.

For his professional work, he received the Award for Distinguished Professional Contributions to Psychology from the A.P.A. in 1972. In a study by Steven J. Haggbloom and colleagues using six criteria such as citations and recognition, Rogers was found to be the sixth most eminent psychologist of the 20th century and second among clinicians, only to Sigmund Freud. Based on a 1982 survey of 422 respondents of U.S. and Canadian psychologists, he was considered the most influential psychotherapist in history (Freud ranked third).

Rogers was born on January 8, 1902, in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. His father, Walter A. Rogers, was a civil engineer, a Congregationalist by denomination. His mother, Julia M. Cushing, was a homemaker and devout Baptist. Carl was the fourth of their six children.

Rogers was intelligent and could read well before kindergarten. Following an education in a strict religious and ethical environment as an altar boy at the vicarage of Jimpley, he became rather isolated, independent, and disciplined. He acquired knowledge and an appreciation for the scientific method in a practical world. At the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he was a member of the fraternity Alpha Kappa Lambda, his first career choice was agriculture, followed by history and then religion.

At age 20, following his 1922 trip to Peking, China, for an international Christian conference, Rogers started to doubt his religious convictions. To help him clarify his career choice, he attended a seminar titled "Why am I entering the Ministry?" After this, he decided to change careers. In 1924, he graduated from the University of Wisconsin, married Helen Elliott (a fellow Wisconsin student whom he had known from Oak Park), and enrolled at Union Theological Seminary (New York City).

Sometime later, he reportedly became an atheist. Although he was referred to as an atheist early in his career, Rogers was eventually described as agnostic. However, in his later years, it is reported he spoke about spirituality. Thorne, who knew Rogers and worked with him on a number of occasions during his final ten years, writes that "in his later years, his openness to experience compelled him to acknowledge the existence of a dimension to which he attached such adjectives as mystical, spiritual, and transcendental." Rogers concluded that there is a realm "beyond" scientific psychology, a realm he came to prize as "the indescribable, the spiritual."

After two years, Rogers left the seminary to attend Teachers College, Columbia University, obtaining an M.A. in 1927 and a Ph.D. in 1931. While completing his doctoral work, he engaged in child study. In 1930, Rogers served as director of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in Rochester, New York. From 1935 to 1940, he lectured at the University of Rochester and wrote The Clinical Treatment of the Problem Child (1939), based on his experience in working with troubled children. He was strongly influenced in constructing his client-centered approach by the post-Freudian psychotherapeutic practice of Otto Rank, especially as embodied in the work of Rank's disciple, noted clinician, and social work educator Jessie Taft.

In 1940 Rogers became a professor of clinical psychology at the Ohio State University, where he wrote his second book, Counseling, and Psychotherapy (1942). In it, Rogers suggests that by establishing a relationship with an understanding, accepting therapist, a client can resolve difficulties and gain the insight necessary to restructure their life.

In 1945, Rogers was invited to set up a counseling center at the University of Chicago. In 1947, he was elected president of the American Psychological Association. While a professor of psychology at the University of Chicago (1945–57), Rogers helped establish a counseling center connected with the university and there conducted studies to determine his methods' effectiveness. His findings and theories appeared in Client-Centered Therapy (1951) and Psychotherapy and Personality Change (1954). One of his graduate students at the University of Chicago, Thomas Gordon, established the Parent Effectiveness Training (P.E.T.) movement. Another student, Eugene T. Gendlin, who was getting his Ph.D. in philosophy, developed the practice of Focusing based on Rogerian listening.

In 1956, Rogers became the first president of the American Academy of Psychotherapists. He taught psychology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison (1957–63), during which time he wrote one of his best-known books, On Becoming a Person (1961). A student of his there, Marshall Rosenberg, went on to develop Nonviolent Communication.

Rogers and Abraham Maslow (1908–70) pioneered a movement called humanistic psychology, which reached its peak in the 1960s. In 1961, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Rogers was also one of the people who questioned the rise of McCarthyism in the 1950s. In articles, he criticized society for its backward-looking affinities.

Best author’s book