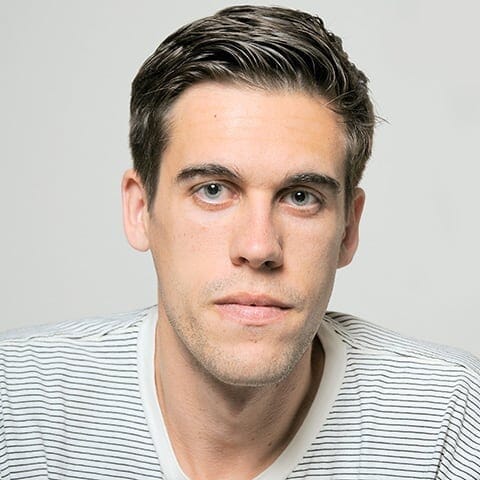

author

authorDiscover the Best Books Written by Saul D. Alinsky

Saul David Alinsky (January 30, 1909 – June 12, 1972) was an American community activist and political theorist. His work through the Chicago-based Industrial Areas Foundation, helping poor communities organize to press demands upon landlords, politicians, economists, bankers, and business leaders, won him national recognition and notoriety. Responding to the impatience of a New Left generation of activists in the 1960s, in his widely cited Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer (1971), Alinsky defended the arts both of confrontation and of compromise involved in community organizing as keys to the struggle for social justice.

Beginning in the 1990s, Alinsky's reputation was revived by commentators on the political Right as a source of tactical inspiration for the Republican Tea Party Movement and, subsequently, by virtue of indirect associations with both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, as the alleged source of a radical Democratic political agenda. While criticizing the political Left for an aversion to broad ideological goals, Alinksy has also been identified as an inspiration for the Occupy movement and campaigns for climate action.

Saul Alinsky was born in 1909 in Chicago, Illinois, to Russian Jewish immigrant parents, the only surviving son of Benjamin Alinsky's marriage to his second wife, Sarah Tannenbaum Alinsky. His father started out as a tailor, then ran a delicatessen and a cleaning shop.

Both parents were strict Orthodox. Alinsky describes himself as being devout until the age of 12, the point at which he began to fear his parents would force him to become a rabbi. Although he had "not personally" encountered "much antisemitism as a child," Alinsky recalled that "it was so pervasive . . . you just accepted it as a fact of life." Called up for retaliating against some Polish boys, Alinsky acknowledged one rabbinical lesson that "sank home."

"It's the American way . . . Old Testament . . . They beat us up, so we beat the hell out of them. That's what everybody does." The rabbi looked at him for a moment and said quietly, "You think you're a man because you do what everybody does. But I want to tell you something great: 'where there are no men, be thou a man'". Alinsky considered himself an agnostic, but when asked about his religion, he would "always say Jewish."

In 1926, Alinsky entered the University of Chicago. He studied in America's first sociology department under Ernest Burgess and Robert E. Park. Overturning the propositions of a still ascendant eugenics movement, Burgess and Park argued that social disorganization, not heredity, was the cause of disease, crime, and other characteristics of slum life. As the passage of successive waves of immigrants through such districts had demonstrated, it is the slum area itself, and not the particular group living there, with which social pathologies were associated.

Yet Alinsky claimed to be unimpressed: what "the sociologists were handing out about poverty and slums"—"playing down the suffering and deprivation, glossing over the misery"—was "horse manure." The Great Depression put an end to an interest in archaeology: after the stock-market crash, "all the guys who funded the field trips were being scraped off Wall Street sidewalks." A chance graduate fellowship moved Alinsky on to criminology. For two years, as a "nonparticipant observer," he claims to have hung out with Chicago's Al Capone mob (he explains that, as they "owned the city," they felt they had little to hide from a "college kid").

Among other things about the exercise of power, he says they taught him "the terrific importance of personal relationships." Alinsky took a job with the Illinois State Division of Criminology, working with juvenile delinquents and at the Joliet State Penitentiary. He recalls it as a dispiriting experience: if he dwelt on the contributing causes of crime, such as poor housing, racial discrimination, or unemployment, he was labeled a "Red."

Best author’s book